De-dollarization: U.S. Sanctions and Geopolitics Challenge Dollar's Dominance

(Pic Courtesy: Daniel McDowell)

The global balance of financial power has been evolving, as countries like Russia and China actively work toward establishing alternative reserve currency systems that challenge the U.S. dollar's dominance.

This phenomenon, known as de-dollarization, has been fueled by an increase in U.S. sanctions and the resulting political risks these countries face. In September of the previous year, Mikhail Ulyanov, the Russian Permanent Representative to International Organizations in Vienna, stated that Western countries had imposed around 11,000 different sanctions on Russia. However, he added that these measures largely went unnoticed by the Russian populace. During times of conflict, it's difficult to take official statements at face value. Sanctions are indeed affecting Russia, but the true extent of the damage is hard to measure. The aviation sector in Russia, for one, has been significantly impacted by Western sanctions. In August of the previous year, Reuters reported that Russian airlines, including the state-controlled Aeroflot, were dismantling aircraft to obtain spare parts that they could no longer afford due to sanctions. As a result of several incidents occurring in Russia's aviation sector in early 2023, there are growing concerns regarding flight safety in the country.

As the U.S. continues to leverage its financial power to punish adversaries, countries with potentially vulnerable positions are exploring ways to loosen their dependence on the dollar, aiming to mitigate the impact of these sanctions. While escaping the dollar's grip is no easy task, the growing awareness of its political vulnerabilities has led to various efforts to create alternative financial systems.

At a recent summit, Chinese President Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin committed to "significantly increase" trade between their nations by 2030. Additionally, President Putin expressed his support for broader globalization of the yuan (also known as the Renminbi) in an effort to reduce the influence of the U.S. dollar.

In a conversation with Daniel McDowell, Associate Professor of Political Science at Syracuse University, Beroe sought insight into the current state of the de-dollarization trend. Daniel's newly published book, "Bucking the Buck: U.S. Financial Sanctions and the International Backlash against the Dollar," delves into the escalating international resistance to the U.S. dollar, considering the rise in sanctions and the tense geopolitical climate.

It was 3 p.m. in Syracuse, New York, when Daniel received Beroe's video call.

Congratulations on your timely new book, as it addresses the ongoing efforts of Russia and China to create an alternative reserve currency system to counter dollar dominance. Could you please provide a brief overview of the key arguments presented in your book?

To clarify, the majority of the book was completed before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, with the final revision taking place approximately six or seven months into the war.

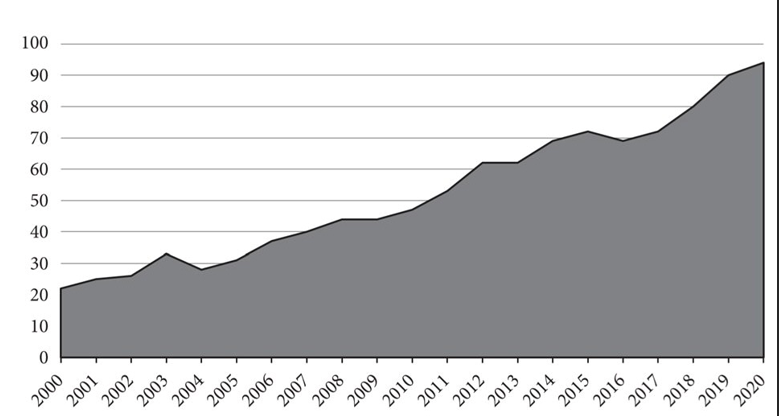

The book, which primarily focuses on the period from 2008 to 2020, argues that as the U.S. employs more sanctions, it generates increased political risk, which is unevenly distributed among countries. Some nations perceive themselves as being at a low or even zero risk of being sanctioned, while others view themselves as having moderate to high risk. This creates incentives for at-risk states to develop alternative systems, engaging in what the book refers to as "anti-dollar policies."

Although escaping the dollar's grip is challenging, governments today are more aware of their vulnerability to the dollar and its political implications. As a result, they attempt various strategies to loosen that grip, with some experiencing modest success. For example, Russia sold off more than 20% of its dollar reserves and invested more in Renminbi (RMB) and gold before the invasion.

Furthermore, countries that recognize their activities could land them on the U.S. sanctions list, or be impacted by U.S. sanctions on their trading partners, may try to de-dollarize their transactions. A notable example is India, which started paying for Russian goods in rubles after the U.S. State Department listed potential Russian defense companies for future sanctions. Despite higher costs and reduced efficiency, this approach provides greater political security.

Figure 1: Sanctions-Related Executive Orders (SREOs) 2000-2020. The figure presents annual count data on the number of active Executive Orders instructing the U.S. Treasury to enforce a financial sanctions program. Each program targets a suite of specially designated nationals (SDNs).

(Source: “Bucking the Buck” by Daniel McDowell)

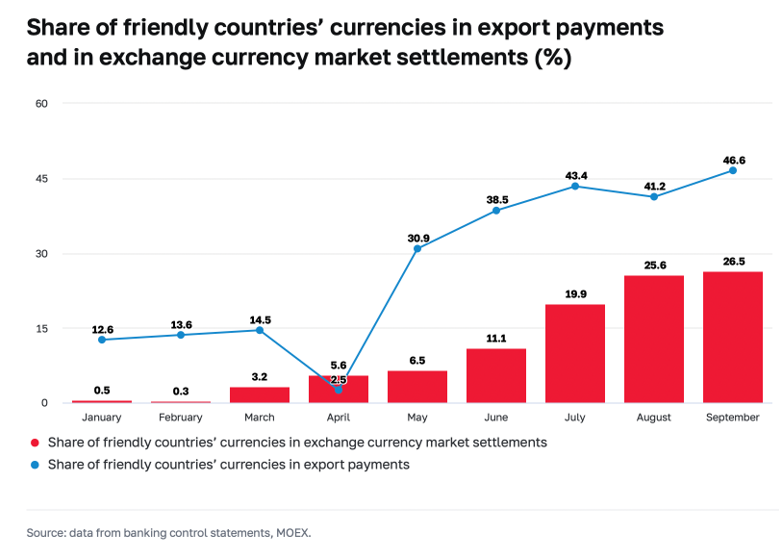

Figure 2: Currency Composition of Settlements for Russian Goods and Services (percent of total)

(Source: The Central Bank of Russia)

In my research, I mostly found discussions about de-dollarization coming from countries such as China, Russia, and India. I didn't see many working papers from the U.S. academia on this topic. However, things are beginning to change. Fareed Zakaria, a respected media personality, recently wrote an opinion piece in the Washington Post, highlighting the same argument you've presented, that geopolitics and sanctions are starting to negatively impact the dollar. Based on your experience, is it rare for this subject to be discussed in the U.S.?

Over the past 8 to 10 years, some scholars have explored the potential of the Chinese yuan or renminbi to become a significant international currency. I am among those who have written papers on this topic, including discussions on sanctions and de-dollarization. While not widely studied, other researchers have also shown interest in this area, with relevant work in economics and political science that focuses on the internationalization of China's currency.

Looking further back, some research from the late 90s and early 2000s explored the euro, but those discussions were short-lived. The current conversation on de-dollarization is more about countries reacting against the United States and the dollar, rather than moving specifically toward China's currency. This shift in focus is relatively new.

In my field of international relations within political science, discussions on this topic started to emerge about five to seven years ago, with mentions of potential reactions against the dollar due to the politicization of sanctions. While full studies were not yet available, the idea was being introduced.

One noteworthy academic is Juliet Johnson, who wrote a paper in 2008 that looked at Russia's efforts to reduce its reliance on the dollar. Her work focused on Russia's response to the Iraq War and deteriorating U.S. relations. However, more comprehensive discussions on de-dollarization began around 2015-2016.

While I have contributed significantly to this field, I do not expect to be the last to do so. It is crucial for researchers to continue examining this important topic.

China has been promoting its currency for trade purposes, encouraging exporters to invoice in yuan and offering incentives. However, even with the massive export industry, the yuan, or the Renminbi (RMB), has not reached the same level of prominence as the dollar or euro. Despite running large trade surpluses, China's currency is not fully convertible, which may play a role. What are your thoughts on why the yuan hasn't gained more traction in international trade, considering the potential currency risk benefits?

Interestingly, Japan in the 1980s and 1990s serves as a past example of a dynamic global economy, similar to China today. Despite this, Japanese companies primarily invoiced in dollars, and the yen never really became a prominent trade settlement currency. China, however, has made more efforts to encourage the use of its currency than Japan did. The question remains, why hasn't it caught on?

There are two perspectives on this matter. Firstly, changes like this occur gradually due to the strong network effects and incentives to use dollars. Most firms worldwide are accustomed to using dollars, and shifting away from this practice is challenging. Competitive pressures and potential volatility in pricing also play a role in maintaining the status quo. From this viewpoint, China's attempts to internationalize the renminbi (RMB) will take time, and progress will be slow.

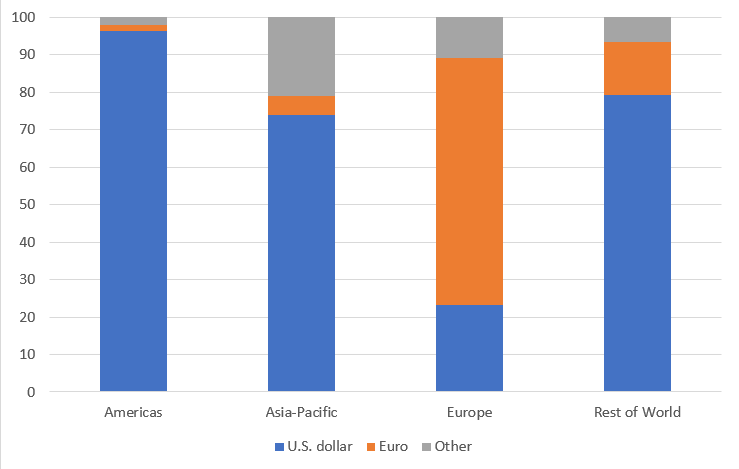

Currently, about 20% of China's trade is settled in its own currency. While this is a significant increase from 15 years ago, it means that the majority of its trade is still settled in dollars. Additionally, there is no evidence that countries outside of China are using the RMB for their own trade.

The second perspective points out that the RMB is not a convertible currency and that China's capital account remains closed. This makes it difficult for foreigners to exchange RMB for other currencies or invest in Chinese assets. Furthermore, geopolitical factors may deter foreign individuals and firms from holding assets in RMB, pointing to lack of trust.

Both political and economic factors contribute to the slow adoption of the RMB as an international currency. China's efforts to promote its currency's international use are hindered by its reluctance to liberalize its financial policies and open up to foreign investment.

Figure 3: Share of export invoicing

(Source: IMF Direction of Trade; Central Bank of the Republic of China; Boz et al. (2020); Board staff calculations.)

You mentioned trust, which is indeed the foundation of any financial system. The U.S. treasuries scores high on trust, which is important for a reserve currency. Can you list some key characteristics of a reserve currency based on your research? Some factors that come to my mind include full convertibility, a strong legal framework, a liberal democracy, and a thriving insurance sector that is willing to cover currency risk without second thoughts. What do you think are the essential characteristics for a currency to qualify as a reserve currency, without which it cannot achieve that status?

There is a substantial body of literature on this topic, primarily in economics, which also intersects with my own work. Two key factors contribute to a currency's appeal as a reserve asset: confidence and convenience.

Confidence refers to the stable value of the currency, not necessarily a fixed exchange rate. For a currency to be attractive to investors, including foreign central banks and bondholders, there must be assurance that its value will not undergo highly volatile fluctuations.

Convenience encompasses several aspects, such as market liquidity. For example, when buying U.S. Treasury bonds, investors consider how easily they can convert those bonds back into cash or find a buyer when they decide to sell. This applies to both individual and institutional investors. The depth of the market is crucial, and the U.S. financial markets, particularly Treasury bond markets, stand out due to their enormous size. These markets can absorb vast amounts of capital, as the U.S. government issues significant amounts of debt.

The convenience factor also includes the ease with which investors can convert assets to cash or vice versa, due to the active and substantial secondary markets. Furthermore, investors have confidence in the U.S. government's commitment to not default on its debt, as it has never done so before.

A fitting analogy would be the concept of a company store. In the 19th century America, coal mining towns had mining companies that paid miners with their own company currency, which could only be used at the company-owned store. This exploitative system eventually became illegal. Similarly, being paid in a currency without international value is like having a gift card or company store currency, limiting its usefulness.

In summary, the main factors contributing to a currency's appeal as a reserve asset are confidence in its stable value and the convenience of using it in well-functioning, liquid markets.

Could one reason for the dollar's dominance be historical, since the modern financial system originated in the West and was further developed by the U.S.? The current fiat monetary system was fine-tuned by the U.S., rather than originating in countries like China or India. How can this be dislodged?

You raise an excellent point, which touches on the concept of first-mover advantage. The United States established the system that now benefits its own currency, enabling the U.S. government to borrow and issue debt with seemingly unlimited demand. Once economies of scale and network effects take hold, with everyone considering the dollar as the safe asset and using it for trade, it becomes challenging to dislodge this dominance.

An analogy can be drawn to Facebook and its 2011 competitor, Google Plus. While Google Plus might have been superior in some ways, it couldn't compete with Facebook's established user base. This network effect, where dollar dominance perpetuates itself, makes it difficult to challenge until a significant shock occurs that disrupts this dominance.

The dollar's dominance increased after the Bretton Woods collapse, and the global economy became dollarized. Regarding your book on sanctions, companies are trying to de-risk their supply chains by avoiding sanctions, but you argue that these sanctions create new risks. Could you explain how sanctions themselves create risk?

The key point here is that sanctions introduce political risk, which is distinct from the economic risks typically considered when choosing a currency for international transactions or investments, such as foreign exchange risk and default risk. Financial sanctions have become more frequent since the early 2000s, with the U.S. increasingly using access to the dollar system as a coercive tool.

For foreign governments with strained relations with the U.S., the dollar may be appealing economically due to its low cost, availability, and efficient services. However, politically, it could be risky, as seen with businesses in Iran and Venezuela being cut off from the dollar system through U.S. executive orders. Although U.S. Treasuries are valuable due to their stable value and liquid market, their worth is diminished if the U.S. government freezes your assets and you cannot access them. Thus, political factors can render the economic value of the dollar useless if you end up on the wrong side of the U.S. government.

There's a recurring theme in certain sections of the international media about the polarized domestic political situation in the U.S. posing a risk to the dollar. Did you cover the impact of the domestic political situation on the dollar in your book?

No, I didn't cover the domestic political situation in my book, but you're right that it has been a talking point. For instance, between 2011 and 2013, there were battles in Congress over the debt ceiling, which some believed hurt the dollar's reputation. However, when Standard & Poor's cut the U.S. credit rating, it had no effect on U.S. borrowing costs. This demonstrates the dollar's dominance in the global market.

While I believe that issues like the debt ceiling and political brinkmanship are bad for the dollar, they haven't had significant impacts so far. My book is focused on sanctions and their effects on the dollar's appeal, rather than domestic politics. Nevertheless, it's an interesting topic worth considering.

Related Insights:

View All

Get more stories like this

Subscirbe for more news,updates and insights from Beroe